Woven into Le Va’s touch is a curiosity. His touch exhibits this curiosity by means of his mastery and mistakes; these mistakes being the essential disparate element in all great works. Often these disparate marks become the vital continuo of his drawings encapsulated in the frame of the sheet. The presence of an orchestrated field of movement contrasts below a finessed Two Part Invention as in the Study for Sculpture in Two Parts from 1991 or in the orchestral-like drawings Bunker Coagulations from 1996. There is Bravura here.

Seeing for the first time the geometry of the German bunkers on Île de Ré and the more monolithic concrete volumes on the coast of Soulac-sur-Mer, France, one immediately recognizes the formal calculations that become aesthetic. The best angle for deflection of armaments has a correlation to physics which in itself is beautiful. There is a relationship between and among the body and these ominous concrete geometries and as in Île de Ré where the ocean is reclaiming these forms the relationships change. As some of the bunkers rest vertically on the edge as the sea steals away the sand foundation one can see Le Va’s wall relief sculptures affects. In the drawings his interests are not perspectival. Instead the viewer is offered something far more compelling, access to a feeling of a form.

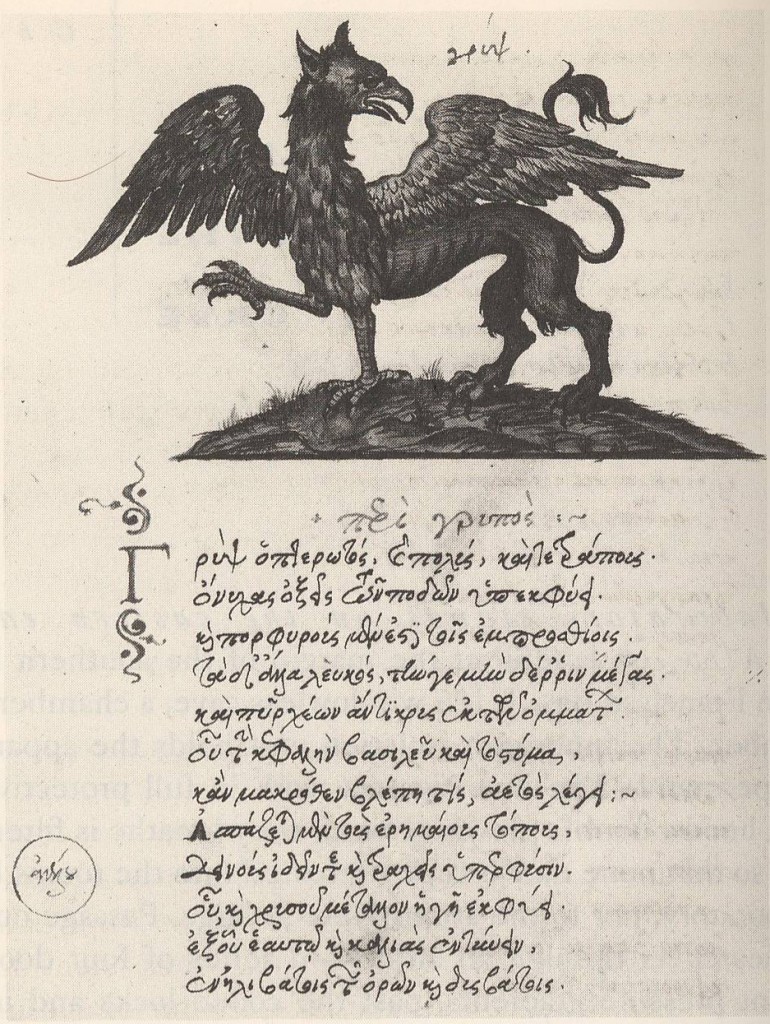

From the earliest work to present, Le Va has been interested in these relationships. In a work from 1968, entitled Wash, one finds an obvious contrapuntal relationship albeit very different from later work. At first, this visual relationship between text and image may seem trivial, but upon considering this notion carefully, one finds a common thread to something as remote as illuminated medieval manuscripts where images float above a ground of text. Le Va’s relationship to drawing has intensified since the 1960s, and the works have developed into impassioned series of drawings each having its own distinct tenor.

Le Va prefers to intellectually and physically move through this world experiencing form, from the conscription of wood to a dowel to a crystal truncated into an isotope or the span of his front heel to his back. The dynamic levels fluctuate, yet every work implies movement. No drawing Le Va crafts sits idle. One could even consider the rhythmic sense-images of Dylan Thomas’s poem, The force that through the green fuse drives the flower. Here a shared immediacy is felt:

The force that through the green fuse drives the flower

Drives my green age; that blasts the roots of trees

Is my destroyer.

And I am dumb to tell the crooked rose

My youth is bent by the same wintry fever.

The force that drives the water through the rocks

Drives my red blood; that dries the mouthing streams

Turns mine to wax.

And I am dumb to mouth unto my veins

How at the mountain spring the same mouth sucks.

The hand that whirls the water in the pool

Stirs the quicksand; that ropes the blowing wind

Hauls my shroud sail.

And I am dumb to tell the hanging man

How of my clay is made the hangman’s lime.

The lips of time leech to the fountain head;

Love drips and gathers, but the fallen blood

Shall calm her sores.

And I am dumb to tell a weather’s wind

How time has ticked a heaven round the stars.

And I am dumb to tell the lover’s tomb

How at my sheet goes the same crooked worm.

Consistent with his description of Mr. Le Va’s works as having two sides—“[o]ne side we see, the other requires us to listen”—so it is with Mr. Mike’s essay: on the surface it offers insights into Mr. Le Va’s work specifically, while on another level it provides insights into the mind of an artist during the creative process.

Mr. Mike’s essay is personal and intimate. It bespeaks an intimate understanding of Mr. Le Va’s work as well as Mr. Le Va himself. Reading the essay, one gets the impression that Mr. Mike considers both Mr. Le Va and his works old friends with whom he has spent many hours conversing and exchanging ideas. Mr. Mike obviously hears the music that silently plays in Mr. Le Va’s works and has the unique ability to make his readers hear that music through his essay. His essay could easily function as an essential companion to Mr. Le Va’s work that would enrich the experience of viewing it for casual viewers as well as experts.

While revealing an intimate knowledge of Mr. Le Va and his works, Mr. Mike’s essay also offers a distinctive insight into the creative process. He seamlessly relates how Mr. Le Va’s works interweave elements of physics, geometry, poetry, and music; in the process of relating these diverse considerations to Mr. Le Va’s works, one can tell that Mr. Mike has grappled with each of them in composing his own works. His essay calls upon everyone—from casual observers to working artists—to look beyond the surface of an artwork and consider the diverse, sometimes contradictory elements that inspired and directed the artist in creating the work.

In the end, Mr. Mike’s essay is an important comment not only upon Mr. Le Va’s art but also upon understanding artists and the art they create. Like the art he describes, Mr. Mike’s essay has multiple layers requiring careful study and consideration from a broad range of perspectives. No matter how many times one reads Mr. Mike’s essay, it always offers something new to ponder.